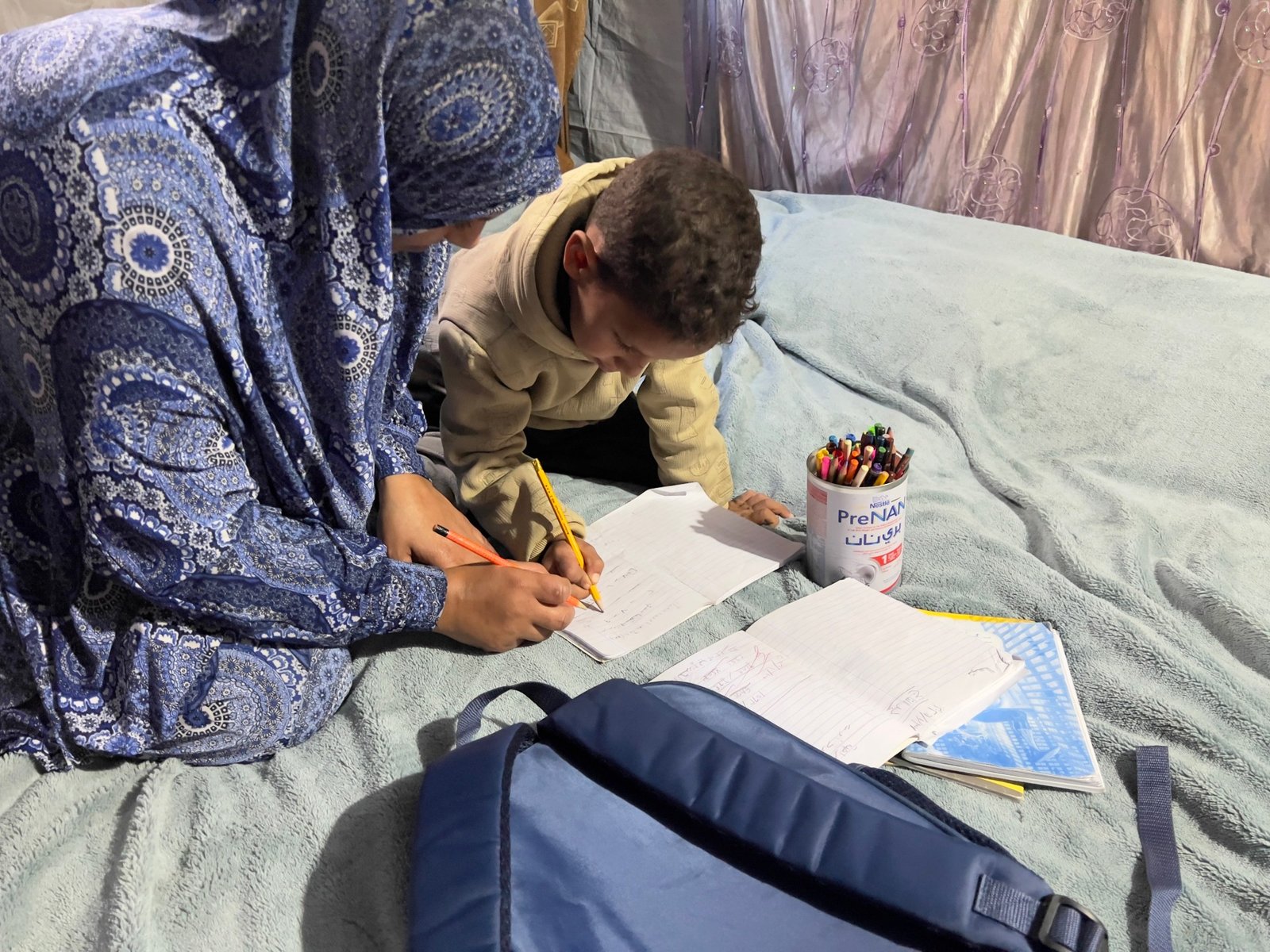

Nuseirat, Gaza Strip – Nibal Abu Armana sits in her tent, where she has been teaching her seven-year-old son, Mohammed, basic literacy and numbers.

Nibal, a 38-year-old mother of six, is forced to rely on the dim light from a battery-powered LED lamp.

Recommended Stories

list of 3 itemsend of list

After two hours, Nibal and Mohammed’s eyes are exhausted.

This is what education is like for many in Gaza. The majority of Palestinians in the enclave live like Nibal and her family: displaced and forced to survive in temporary shelters barely fit for habitation.

But Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, which has killed more than 70,000 Palestinians, has gone on for more than two years, and the necessary reconstruction is unlikely to happen any time soon.

The majority of school buildings have been damaged or destroyed by Israel, along with the majority of other structures in Gaza. Many of the school structures that remain are now used as shelters for displaced families.

And students – both children at schools and young adults at universities – have largely missed any form of regular education since the war began in October 2023.

“My children used to have a routine before the war: wake up early, go to school, get back home, have lunch, play, write homework, and sleep early,” Nibal told Al Jazeera. “There was a sense of discipline.”

Now, she said, her children’s days are structured around their basic needs: sourcing water, getting meals from a charity kitchen, and finding something to burn on the fire for cooking and warmth. After all of that, there is little time left in the day to study.

Nibal, originally from the Bureij camp but now living in central Gaza’s Nuseirat, said her children struggled, especially at the start of the war, when all forms of education stopped for months.

And now, even though circumstances are getting better, it is hard to catch up. Many older children, who have missed out on education at a vital period of their lives, are unwilling to resume their studies.

“My eldest son, Hamza, is 16 years old, and he entirely rejects the idea of going back to school,” Nibal said. “He has been cut off from learning for so long and lived in displacement that he lost interest in education. He has new responsibilities. He works with his dad as a porter, helping people carry their aid boxes. He focuses on working to get money to buy food for us and buy himself clothes.”

“He grew up before his time; he bears the responsibilities and thinks like a parent would for his youngest siblings,” she said.

Nibal’s second son, 15-year-old Huzaifa, is eager to keep learning, but uncertain of his future, as he thinks it will take him years to make up for the time he has lost being unable to study properly.

For now, he is studying, but he is forced to attend classes in a makeshift tent classroom.

“I feel tired sitting on the ground, and my back and neck ache while writing and looking at the teachers,” Huzaifa said.

Attacks on education

Since Israel’s genocidal war on Gaza, 745,000 students have been out of formal schooling, including 88,000 higher education students who have been forced to put their studies on hold.

Even with a “ceasefire” being in place since October, which Israel continues to violate, more than 95 percent of the significantly damaged school buildings require rehabilitation or reconstruction, according to UNESCO satellite damage assessments. At least 79 percent of higher education campuses and 60 percent of vocational training centres are also damaged or destroyed.

Ahmad al-Turk, the dean of public relations and assistant to the president of the Islamic University of Gaza, said that Israel has been deliberately attacking education.

“Targeting professors affects future generations, especially given the experience and skills these professors possess in their fields of specialisation,” al-Turk said. “There is no doubt that the absence of competent professors negatively affects students’ achievement, as well as the research process in the future.”

This is particularly worrying for Raed Salha, a professor at the Islamic University and an expert on regional and urban planning.

“University expertise is not something that can be replaced quickly,” he said. “It is cumulative knowledge built through years of teaching and research. Losing it – whether through death, forced displacement, or prolonged disruption – is a devastating loss for students, academic institutions, and society as a whole.”

Most families and university students also struggle with the online education system, as it is difficult to afford to buy electronic devices and mobile phones, even before taking into account the weak internet connection in Gaza.

“Teachers are trying to teach; students are trying to follow, but the tools are almost nonexistent,” Salha said.

“We cannot recreate the experience of students leaving home in the morning, meeting friends, sitting in university courtyards, libraries, laboratories, or participating in activities and events,” he said. “This experience shaped generations of students’ identities and sense of belonging. Today, it is being taken away from them.”

![University students at the Islamic University campus in Gaza City after partially resuming face-to-face learning at IUG [Mustafa Salah/Al Jazeera]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/image00004-1770756852.jpeg?resize=770%2C433&quality=80)

University challenges

University student Osama Zimmo explained that getting used to online learning has been a challenge.

“We became names on screens, not students living a full experience,” the 20-year-old civil engineering student from Gaza City said.

Osama had enrolled to study computer systems engineering at Gaza’s al-Azhar University before the war, and completed the first year of his studies.

But despite his initial passion for that field, it became difficult to continue his studies online once the university shifted to e-learning.

“I found that I didn’t have a laptop, stable electricity, or good internet, and even my phone was old and unreliable,” he said, adding that uncertainty over when the war would end and the impact of artificial intelligence gave him pause about his chosen field.

Eventually, he decided to switch his major, starting a civil engineering degree at the Islamic University, which would involve him relying less on electricity and the internet.

The Islamic University resumed in-person classes in December.

“It was a choice to continue rather than stop; to adapt rather than giving in,” Osama said.

“We study not because the path is clear, but because giving up is exactly what this reality tries to force on us.”